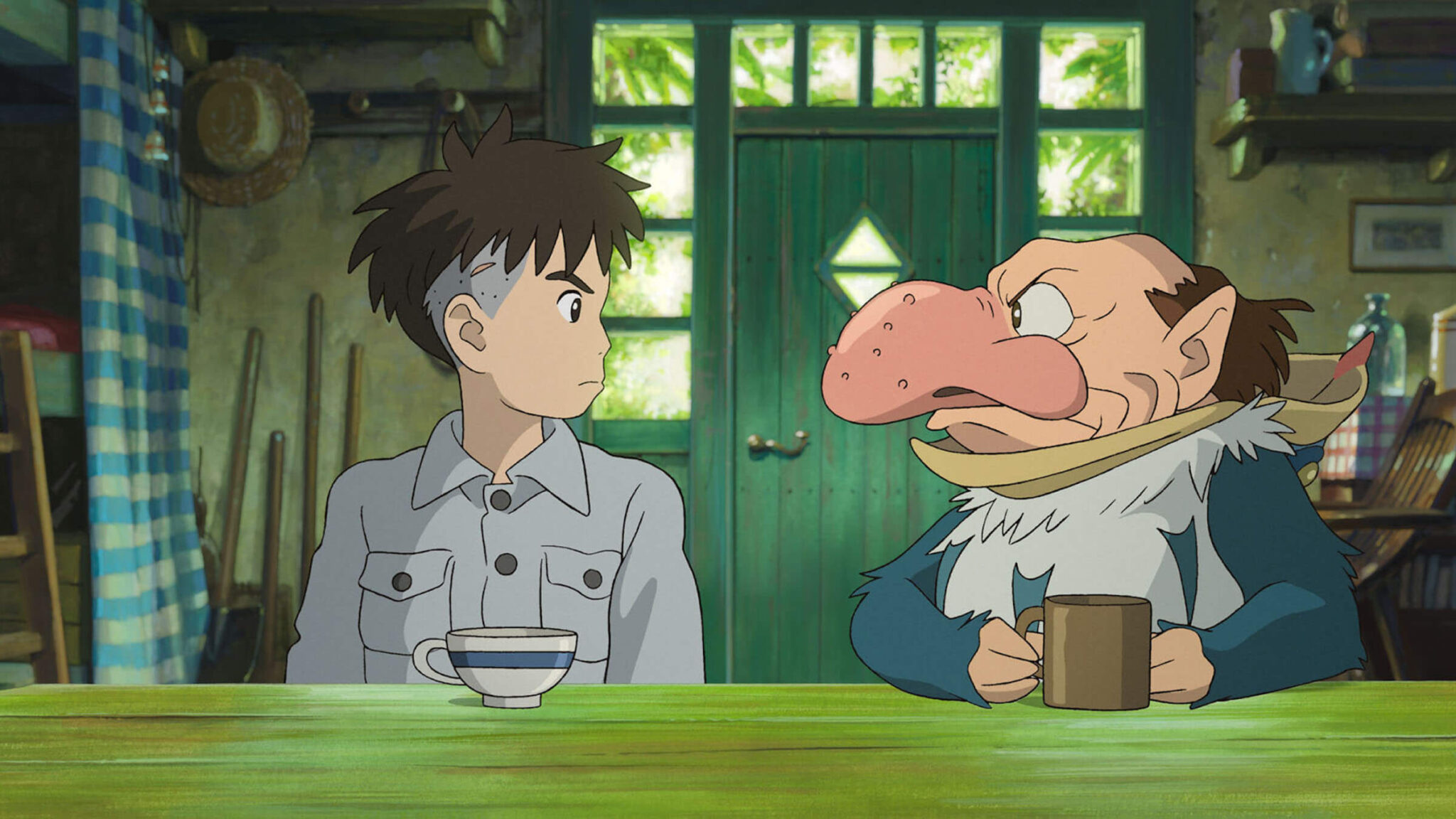

The Craft and Rules of Worldbuilding in Science Fiction & Fantasy

What are the best ways writers can begin the worldbuilding of their science fiction and fantasy stories?

J.R.R. Tolkien created a long-ago land called Middle Earth, full of hobbits, warriors, wizards, kings, elves, orcs, and dwarves.

J.K. Rowling imagined a world parallel to ours, where witches and wizards were educated in the Scottish Highlands and battled in a war between light and dark magic.

George Lucas didn't just conjure a world with Star Wars. He built a whole galaxy full of Jedi, rebels, imperials, aliens, and droids.

Worldbuilding is often defined as the process of constructing an imaginary world within a fictional — and sometimes real — world. Authors and screenwriters build worlds every single time they sit down and imagine a story. Sometimes those worlds are fictional. Other times they are embedded within the real world of the past or present.

But when you build worlds for the genres of science fiction and fantasy, that process is even more vital to creative development because the fanbases of both genres have seen it all.

They've invested hours upon hours of reading and watching fantastical and imaginative worlds unfold before their eyes as heroes and villains battle amidst far away planets, magical landscapes, mystical battlefields, and altered realities.

Inspired by the wisdom of literary and cinematic visionaries like Tolkien, Rowling, and Lucas, with a little guidance and inspiration from the Dungeons & Dragons World Builder's Guidebook, we explore the craft and rules of worldbuilding and how authors and screenwriters can best create worlds for readers and audiences to explore vicariously through the characters created to inhabit them.

Note: Spoilers below for films like The Matrix, Identity, Pan's Labyrinth, etc.

Rivendell in 'The Lord of the Rings' (New Line Cinema)

Table of Contents

The Five Categories of Worlds to Build Within

We start by exploring the five general categories of worlds that writers can build from. Every story is different and calls for a different category of worlds.

Real World Past

- The Middle Ages

- The Wild West

- World War II-era

While not generally utilized in science fiction and fantasy genres, these settings can provide locations and set pieces to introduce the Sci-Fi/Fantasy realm. Look no further than Guillermo Del Toro's Pan's Labyrinth, set within the real world past of WWII, but introduces a fantasy realm.

Real World Present

These types of stories take place within the present world as we know it. However, true worldbuilding takes place through the more microscopic lens of characters, locations, cultures, and societies within our present times. Since science fiction and fantasy elements don't exist within our present real world (that we know of), they have to be introduced. Examples include:

- Ghostbusters

- Back to the Future (then-present and past)

Alternate Reality

These types of stories exist within already-established past and present worlds but offer an alternative version of what we know and remember. Unlike fantasy worlds (see below), there is much less suspension of disbelief by readers and audiences because the science fiction and fantasy elements are grounded by the past and present real worlds they know.

These types of worlds allow writers to explore compelling "What if..." questions.

- What if the world as we know it is actually a computer program (The Matrix)?

- What if the world we are presented with onscreen is actually set within the mind of a killer (Identity)?

- What if the outcome of WWII had been different (The Man in the High Castle)?

Speculative Future

These types of stories are predominantly science fiction worlds where writers conjure speculative futures of science and technology. Examples include:

- Black Mirror

- Star Trek

- The Martian

Fantasy

These types of stories are set in worlds that are constructed entirely within fictional universes. Laws and physics of Earth and space as we know them don't always have to apply. The writer makes up the worlds and the laws and physics within those worlds. Examples include:

- Star Wars

- Lord of the Rings

- The Dark Crystal

These five categories of worlds are where your worldbuilding starts. You can look at them first and then conjure a science fiction or fantasy story from there — or you can take a concept that you have and place them within those foundations.

When you know your world category, you'll know the rules (or lack thereof) that need to be followed during your development and writing process.

- When you're dealing with Real World Present, you're bound by the laws and physics of Earth and space as we know it. Any science fiction and fantasy elements you introduce within our world as a setting must collide with what we know and are familiar with here and now.

- The same can be said within Real World Past. Any changes to the past as we know it are either colliding with the truth or changing our perspective of what we know.

- Alternate Reality worlds live within the constructs of our past and present but introduce intriguing "What if..." elements to create fictional and speculative alternatives.

- For Speculative Future worlds, when characters and concepts exist within a possible future, speculation of science and technology possibilities are explored. However, they are based within the laws and physics of Earth and space as we know them now. Otherwise, they turn closer and closer into fantasy.

- When you create a Fantasy world, the rules are thrown out of the metaphorical window. You can do whatever you'd like as an author or screenwriter.

And sometimes, what's most interesting in worldbuilding is when you create hybrids of these categories.

The Fetus Fields in 'The Matrix' (Warner Bros.)

The Physical and Historical Components of Your World

As the Dungeons & Dragons World Builder's Guidebook states: "Take a moment to consider everything you would have to do in order to record our own planet as a [setting]."

If you were to reverse-engineer the creation of our world, Earth, you would record:

- Seven major continents

- Climates

- Landforms

- Cultures

- Resources

- History

- Beliefs

- Societies

- Uncounted variety of animals and plants

By worldbuilding standards found within science fiction and fantasy worlds, none hold a candle to our own world's complexity.

So when you are creating your story's world, these are the things that you need to take into consideration.

- What does your world look like?

- What kind of climates, landforms, continents, and resources are there?

- What is the history of the world? What has or hasn't happened?

- What are the people like, and what do they believe?

- What type of wildlife and vegetation exists within your world?

The details of your components that you conjure will depend on the category of the world you are creating (see above) and how much detail you want or need to go into within your story, and depending on what platform you're telling it (literary vs. cinematic).

The most detail-oriented world category is Fantasy because you have nothing else to build off of beyond your influences from past imagery and description from stories you've ingested from literature, film, and television.

Using Reader Preconceptions and Assumptions as Shortcuts to Worldbuilding

A big shortcut in fictional writing and worldbuilding is trusting that the reader and audience will fill in the blanks for you. How you accomplish that is by using preconceptions and assumptions that everyone has.

Each reader and audience member has ingested multitudes of storytelling on many different platforms.

- Books/Novels

- Movies

- TV Shows

- Podcasts

- Pictures

- Verbal stories

Use that to your advantage to save you time and effort in the description of your world.

If you want a Middle Ages setting, tell the reader that the story is set in those times. They will immediately call to their preconceptions and assumptions based on what they have experienced in other stories they've encountered throughout their life.

Use phrases like:

- Desert Planet

- Ice planet

- Forest Planet

- Medieval village

- Future city

Offering them universal imagery will help you and the reader relate to the world you're describing without having to go into too much detail of the broad strokes.

Tatooine in 'Star Wars'

Conjuring Your World’s Story Components

Your story's world has four basic story components. These are the narrative elements that help flesh out your world beyond its category rules, physical components, and historical components. In essence, the story components showcase depth within the world and inject the story details that need to inhabit it to capture the attention and imagination of the reader and audience.

Characters

You need a cast of characters to inhabit the world you've created — comprised of protagonists/heroes, supporting characters around them, and antagonists and villains.

Locations

You need a location or locations within your world where the story takes place.

- It could be a single city, village, or town.

- It could be a continent or land that the hero journeys through.

- It could be a galaxy or universe.

Threats

All stories need conflict. And in science fiction and fantasy stories, especially, that means there need to be single or multiple threats that the protagonist or hero is dealing with. This is what gets their story going.

- It could be nature.

- It could be antagonist and villain plots.

- It could be a combination of the two.

Whatever you create, the threats have to create conflict for the characters to overcome.

Journeys

The characters — specifically a hero or protagonist — need to go on physical or spiritual journeys within your stories. This is for any literary or cinematic genre. But with science fiction and fantasy, the journey is vital to the impact it makes on the reader or audience.

Six Development Approaches to Your Worldbuilding

When you have all of the basic physical, historical, and story components of your world, you need to figure out where to start when you envision it.

Here are seven approaches you can take:

- The Macroscopic Approach — This approach starts with the world itself, as far as the physical and historical components. You then try to inject your story components (characters, locations, threats, journeys) into that world.

- The Microscopic Approach — The opposite of the Macroscopic Approach. You start from a specific type of character — or location where the character is present — and work your way out into the world as the character(s) venture out.

- The Sociological Approach — If you have a type of society or culture that you want to feature, you can start with that and eventually introduce your characters. Then you work outwards again to your world.

- The Situation-based Approach — It could be a force of nature, a war between two clans/tribes/forces, a monster, a threat, etc. The situation is introduced, and the characters are revealed. As they deal with the situation (threat), they explore the world around them that you've created.

- The Historical Approach — If you're dealing with a historical event, you can work from there and introduce characters. Or you can create your own fantasy historical event. An easy example would be the history of the One Ring in Lord of the Rings and the battle that was fought for it years before Frodo ever laid eyes on it.

- The Character-based Approach — Sometimes, you conjure single or multiples characters that are so compelling that they deserve worlds to be built around them.

Whatever approach you take, the key is to create a detailed and plausible world within the rules you create and stipulate. Remember:

- When you're dealing with Real World Present and Real World Past, you're bound by the laws and physics of Earth and space as we know it.

- Alternate Reality worlds live within the constructs, laws, and physics of our past and present but introduce intriguing "What if..." elements to create fictional and speculative alternatives.

- For Speculative Future worlds, when characters and concepts exist within a possible future, speculation of science and technology possibilities are explored. However, they are based within the laws and physics of Earth and space as we know them now. Otherwise, they turn closer and closer into fantasy.

- When you create a Fantasy world, the rules are thrown out of the metaphorical window. You can do whatever you'd like as an author or screenwriter.

- Whatever rules you create or adapt to your world, know that you need to stick to them to make your stories and characters plausible, compelling, and engaging.

Happy worldbuilding!

Ken Miyamoto has worked in the film industry for nearly two decades, most notably as a studio liaison for Sony Studios and then as a script reader and story analyst for Sony Pictures.

He has many studio meetings under his belt as a produced screenwriter, meeting with the likes of Sony, Dreamworks, Universal, Disney, Warner Brothers, as well as many production and management companies. He has had a previous development deal with Lionsgate, as well as multiple writing assignments, including the produced miniseries Blackout, starring Anne Heche, Sean Patrick Flanery, Billy Zane, James Brolin, Haylie Duff, Brian Bloom, Eric La Salle, and Bruce Boxleitner, and the feature thriller Hunter’s Creed starring Duane “Dog the Bounty Hunter” Chapman, Wesley Truman Daniel, Mickey O’Sullivan, John Victor Allen, and James Errico. Follow Ken on Twitter @KenMovies

For all the latest ScreenCraft news and updates, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Get Our Screenwriting Newsletter!

Get weekly writing inspiration delivered to your inbox - including industry news, popular articles, and more!